This article was first published in Flipping & Turning magazine. A fantastic publication for old-school tabletop gamers. Highly recommended.

When I first opened the box and held the Traveller rulebooks in my hands back in the late 1970s, I knew I had something special. Created by Marc Miller and published by Game Designers’ Workshop (GDW), Traveller wasn’t just another RPG—it was a revelation. I loved AD&D, but Traveller introduced me to a different experience with a focus on realism, player agency, and open-ended storytelling.

Even after decades and numerous editions, the original Traveller—often called “Classic Traveller”—remains my favorite. It’s a game that feels timeless, a masterpiece of design that still holds up today. This article discusses how Traveller innovated compared to early D&D, its revolutionary mechanics in the RPG landscape, and its evolution over the years.

One note on age: When Traveller came out in 1977, there were basically two kinds of Traveller players. The young and the older ones. The older ones read a lot of the novels that Traveller was inspired by. Dumerest of Terra probably being one of the most important. Players familiar with science fiction novels may view the Third Imperium, the default setting’s interstellar government, as neutral or even benign. The younger ones would see the Imperium as the Empire from Star Wars, the bad guys. I went from a Star Wars guy to one who really got deep into the Imperium as it was written.

The Genius of Classic Traveller: A Game Ahead of Its Time

Let’s start with the original Traveller, the edition that started it all. I bought mine in 1979, although it was released in 1977. Classic Traveller was a breath of fresh air in a hobby dominated by Advanced Dungeons & Dragons dungeon-crawling fantasy. The game stood out not just because it shifted to science fiction, but also due to its unique mechanics, storytelling, and player freedom. has much better quality in terms of printing and paper. GDW had experience in producing wargames and print production, including their own typesetting system, likely a Compugraphic. The original books were all black with white and red lettering. The physical form of this edition is now known as the Little Black Books, or LBB.

Games Within the Game

One of the most iconic features of Classic Traveller is its lifepath character creation system. In contrast to D&D, where you simply roll stats and choose a class, Traveller turns character creation into an exciting adventure. Choose a career—Navy, Merchant, Scout, or another—and roll dice to decide your character’s skills, rank, and life events. Did you get promoted? Did you suffer an injury? Did your character even survive character creation? Yes, your character could die before the game even started, and it was glorious.

This is but one example of the way Traveller approached many of its systems. There were games within the games that you could play without the rest of the system, even without a referee. Character generation was like its own game, and a lot of people had fun with it just by itself. Things like generating subsectors of space, planets, and making credits with your own merchant vessel through trade and commerce were all games within the game that could be played on their own if desired.

No Levels, No Experience Points

Classic Traveller completely eliminated the notion of levels and experience points. Your character didn’t gain power by killing monsters or looting dungeons for items and gold pieces. Instead, progression came through acquiring information, equipment, and wealth. This was a huge game-changer. It shifted the focus away from grinding for XP and toward role-playing, problem-solving, and exploration. Your character was competent from the start, and the game rewarded cleverness and creativity over brute force.

This mechanic also made Traveller much more fun. You didn’t need to spend weeks or months leveling up to feel powerful. You just needed a good plan and a bit of luck.

Characters would “muster out” of whatever service they enlisted in (or were drafted into) and get money (their savings) and various pieces of equipment, such as a sidearm, a ship, or passages. Passages are a ticket to another close-by world. There are three types of passages: low passage (cold sleep with possible risk of death), middle passage (standard accommodations used by most people), and high passage (luxury accommodations with better food and service). Someone with a high passage can bump a passenger using a middle passage if there was no more space on the vessel.

Library Data

The default setting of Traveller is the Third Imperium, and it is incredibly deep. Conveying that to players could be cumbersome. But there was the perfect mechanism for this: Library Data. This is a great way to data dump to the players and have it somewhat mirror what the characters get in-game.

The group usually acquires a ship either during character creation or based on the scenario. One of the programs loaded into the ship’s computer was Library Data. This was represented to the players as an alphabetical listing of entries. With this, the referee would provide existing library data from the two volume Library Data set in the original little black books. The referee could provide extra details about the local planet and any other information players might need during the game. The players might say, “Oh, that was in Library Data. What was that thing again?” They could then find the entry, and one player would read it out. It works well.

Realism and Simulation

Classic Traveller was designed with a level of realism that was unheard of at the time. The game included detailed rules for ship construction, interstellar trade, and even (simplified) fuel consumption. Space travel wasn’t just a backdrop—it was a core part of the game. The “Jump” mechanic required players to plan their journeys carefully since ships could only travel a limited number of parsecs at once. This added a layer of strategy and tension that was absent in early D&D.

I love that Traveller’s character sheets and forms for generating planets and building ships feel like they were made for the characters themselves. The character sheet was designated as TAS Form 2, which stands for the Travellers’ Aid Society personal record form. It sounds very geeky, but forms were important. They added to the depiction of the huge bureaucracy that kept the Imperium running. In fact, one of the original LBB add-on books was Supplement 12: Forms and Charts. Players with a character rated admin-1 or higher had to handle all the paperwork, except for character sheets, for everyone else in our group when I was younger.

Open-Ended Sandbox Play

While D&D often revolved around dungeon crawls and combat encounters, Classic Traveller offered a truly open-ended experience. The game promoted sandbox play, allowing players to explore the galaxy, trade, engage in diplomacy, and build empires. The referee (GM) was provided with tools to generate entire star systems, planets, and alien species, allowing for endless possibilities.

This flexibility was one of Traveller’s greatest strengths. It wasn’t just a game—it was a toolkit for creating your own sci-fi adventures. Whether you sought to embark on a thrilling military campaign, engage in an intricate merchant trading game, or weave a tale of political intrigue, Traveller provided the perfect platform for your adventure.

Add-on Games

This concept was further developed with complete additional games. You could obtain a set of 15mm military miniature rules called Striker (available in little black books), which includes many detailed rules for mercenary actions. The rules included a detailed vehicle design system to build things at pretty much any technological level. One of the first ever published.

Azhanti High Lightning incorporates the fundamental Striker rules while enhancing the experience with unique shipboard environmental rules. Azhanti High Lightning and Striker offer a complete replacement for the more abstract combat rules in Traveller, for both personal and vehicle battles.

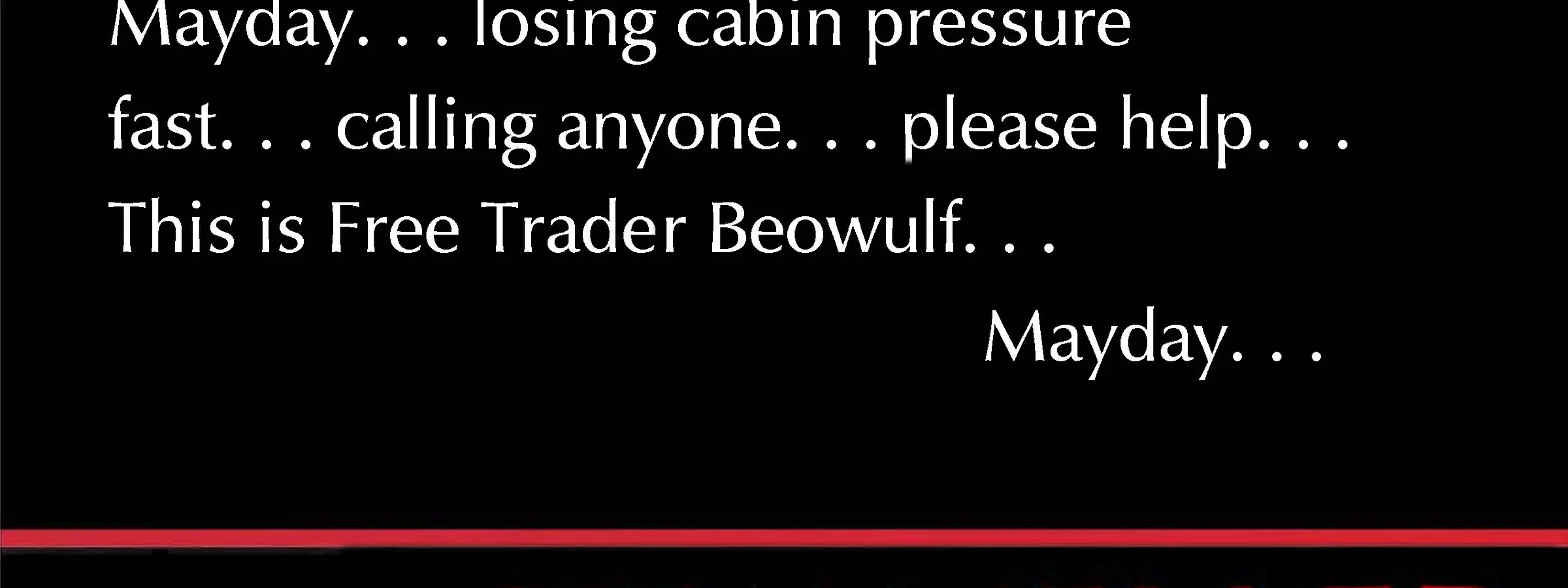

Mayday was a ship-to-ship combat game that streamlined the core LBB vector movement rules for ship combat. Utilizing three counters on a hexagonal grid to monitor vector movement was a groundbreaking concept. One counter shows your current position, another your previous position, and a third predicts your future position based on thrust changes. Quite elegant. The starship combat rules in the core LBB were too complex and often ignored by most players of Classic Traveller.

The Evolution of Traveller: A Mixed Bag

Over the years, Traveller has seen numerous editions, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Although I will always hold Classic Traveller in the highest esteem, it’s important to examine how the game has evolved—and, at times, strayed from its original essence.

MegaTraveller (1987-1991)

MegaTraveller streamlined some of the inconsistencies in Classic Traveller and introduced the “Rebellion Era” setting. While it retained the core mechanics, it added more detailed combat and starship rules. It was a solid update, but it lacked the minimalist charm of the original. Loved the consolidation of the rules, but they decided to blow up the established canon by having the emperor be assassinated and the Imperium break up. I pretend that part never happened, and so did Steve Jackson Games in 1998.

Traveller: The New Era (1993-1996)

This edition introduced the “Virus” storyline, which brought devastation and chaos to the Traveller universe, reshaping its lore and challenging its characters in unprecedented ways. The rules were overhauled to use the GDW House System, which emphasized realism and detail. Hated it.

Marc Miller’s Traveller (T4) (1996)

T4 was a return to the game’s roots, set during the early days of interstellar travel. It introduced new mechanics for character creation and world-building, but was marred by poor editing and production quality. Lame garbage.

GURPS Traveller (1998-2006)

This edition adapted the Traveller setting to the Generic Universal Role-Playing System (GURPS). Loved this one. They also just ignored the stupid rebellion that was triggered by Emperor Strephon being assassinated. In GURPS Traveller, the emperor lives on! Love this edition.

Mongoose Traveller (2008–Present)

Mongoose’s editions revitalized Traveller for a new generation. The first edition streamlined the rules while staying true to the classic feel, and the second edition refined them further. It’s pretty good, I suppose.

Traveller5 (2013)

Created by Marc Miller himself, Traveller5 is a comprehensive and highly detailed version of the game. While it’s impressive in its scope, it is overly complex compared to the elegant simplicity of Classic Traveller.

I have almost every edition of every one of the aforementioned versions of Traveller.

Yeah, it’s a sickness.

Why Classic Traveller Still Reigns Supreme

For me, Classic Traveller is the gold standard. With its minimalist rules, engaging life-path character creation, and limitless gameplay possibilities, this game is not only easy to learn but also utterly addictive. It’s a game that trusts its players to tell their own stories, without getting bogged down in unnecessary complexity.

While later editions have their merits, they often lose sight of what made the original so special. Classic Traveller wasn’t just a game—it was a universe in a box, waiting for you to explore it. And that’s why, after all these years, it’s still my favorite.

Conclusion

Traveller is more than just a game—it’s a testament to the power of imagination and innovation. With its innovative mechanics and lasting impact, it has profoundly influenced the RPG landscape in ways that continue to resonate today. Although I hold a special fondness for Classic Traveller, I deeply appreciate the various editions that have breathed new life into the game and welcomed countless new players across generations. Regardless of whether you’re a seasoned veteran or a newcomer to the hobby, Traveller presents a vast universe of opportunities just waiting to be discovered. And for me, there’s no better way to explore it than with the original still being printed in various forms.

Unfortunately, the reprints are not produced as little black books.

That era is only in the past, and on eBay.